Cname Record vs A Record Differences

- 1.

Wait—Y’all Mean You *Can’t* Just Slap a CNAME on Any Ol’ Domain and Call It a Day?

- 2.

What in Tarnation *Is* an A Record, Anyhow?

- 3.

So Then… What’s a CNAME Record Sneakin’ Around For?

- 4.

Hold Up—Can You Even *Have* a CNAME Without an A Record?

- 5.

What Happens When You Try to Jam ‘Em Both in the Same Slot?

- 6.

Y’all Seen That RFC 1034? ‘Cause It’s Got *Opinions*

- 7.

Real Talk: When Do You *Actually* Use Which?

- 8.

Fun Fact: Some Providers *Fake* CNAMEs at the Root (and It’s Genius)

- 9.

CNAME Chains: The DNS Equivalent of “Hold My Beer”

- 10.

How *We* Keep ‘Em Straight When the Coffee’s Run Out

Table of Contents

cname record vs a record

Wait—Y’all Mean You *Can’t* Just Slap a CNAME on Any Ol’ Domain and Call It a Day?

Ever tried pointin’ your cousin’s hand-me-down ’98 Camry down I-95 during rush hour and wonderin’ why it’s chuggin’ like it’s draggin’ a whole dang trailer? Yeah. That’s what it feels like when folks toss a CNAME record on a root domain like example.com and then get all baffled when the DNS gods start sendin’ smoke signals. CNAME record vs A record? Honey, it ain’t just semantics—it’s the difference between smooth sailin’ and your whole site ghostin’ like it’s been banned from the internet prom. We been in the trenches—debuggin’, diggin’ through zone files, squintin’ at dig outputs at 2 a.m.—and lemme tell ya: misconfigurin’ cname record vs a record is how careers get *lightly* traumatized. Ain’t about bein’ fancy—it’s about knowin’ your tools like you know your grandma’s biscuit recipe: *exactly*, down to the pinch of salt.

What in Tarnation *Is* an A Record, Anyhow?

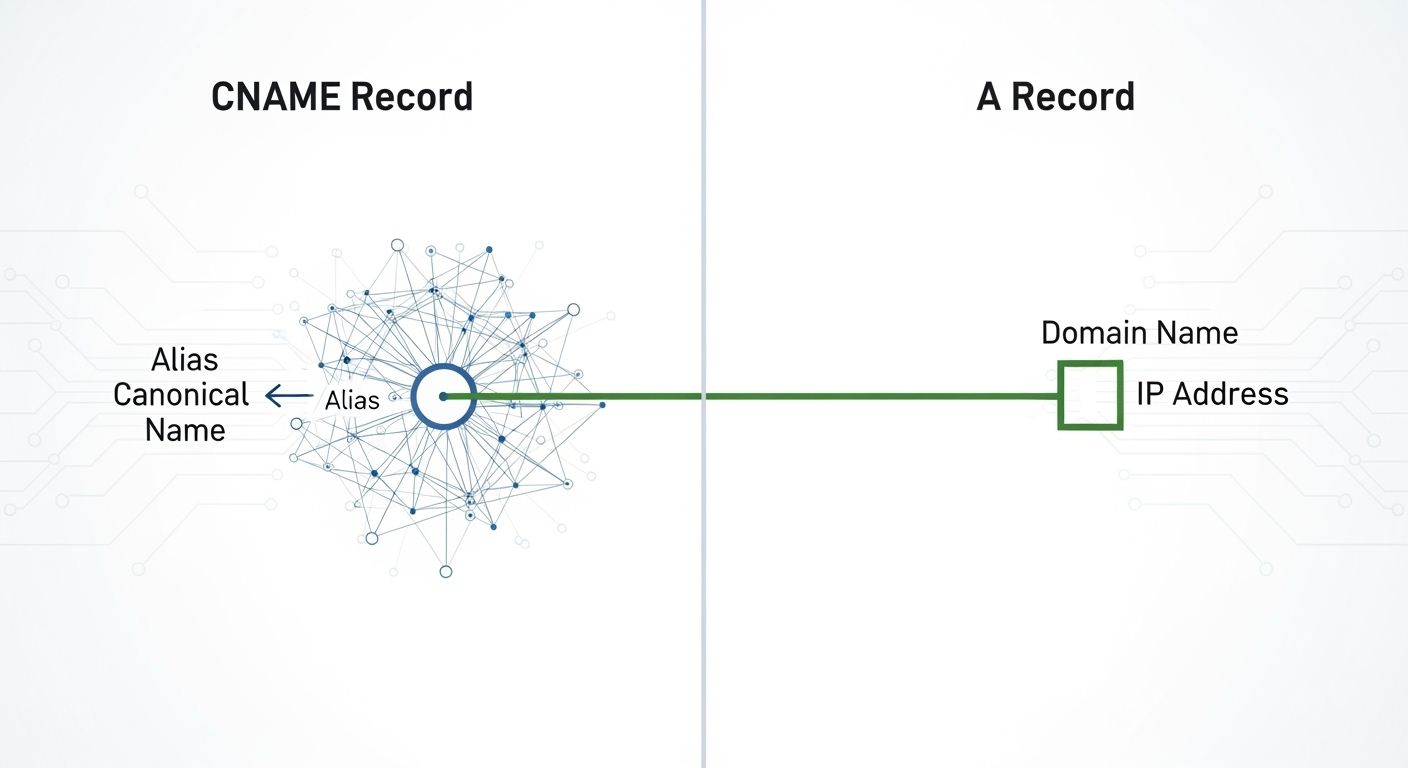

An A record? Lord, bless its heart—it’s the OG. The A stands for “Address,” and in our lil’ DNS universe, that means IPv4. Plain. Simple. No fluff. You type www.peternakdigital.com, your resolver peeps the A record, and *bam*—gets handed an IP like 192.0.2.1. Straight-up street address for the internet. No detours, no forwarding, no “ask my cousin Vinny” nonsense. Just: *Here. This box. Right here.* The cname record vs a record showdown starts here—’cause while the A record *is* the destination, the CNAME’s just a polite note sayin’, *“He ain’t home—try knockin’ over at api.peternakdigital.com instead.”* And listen: according to Cloudflare’s 2024 DNS Survey, over 73% of misconfigured root domains? Yeah. They tried puttin’ a CNAME where an A record *should’ve* been standin tall like a lighthouse in a storm. Oof.

So Then… What’s a CNAME Record Sneakin’ Around For?

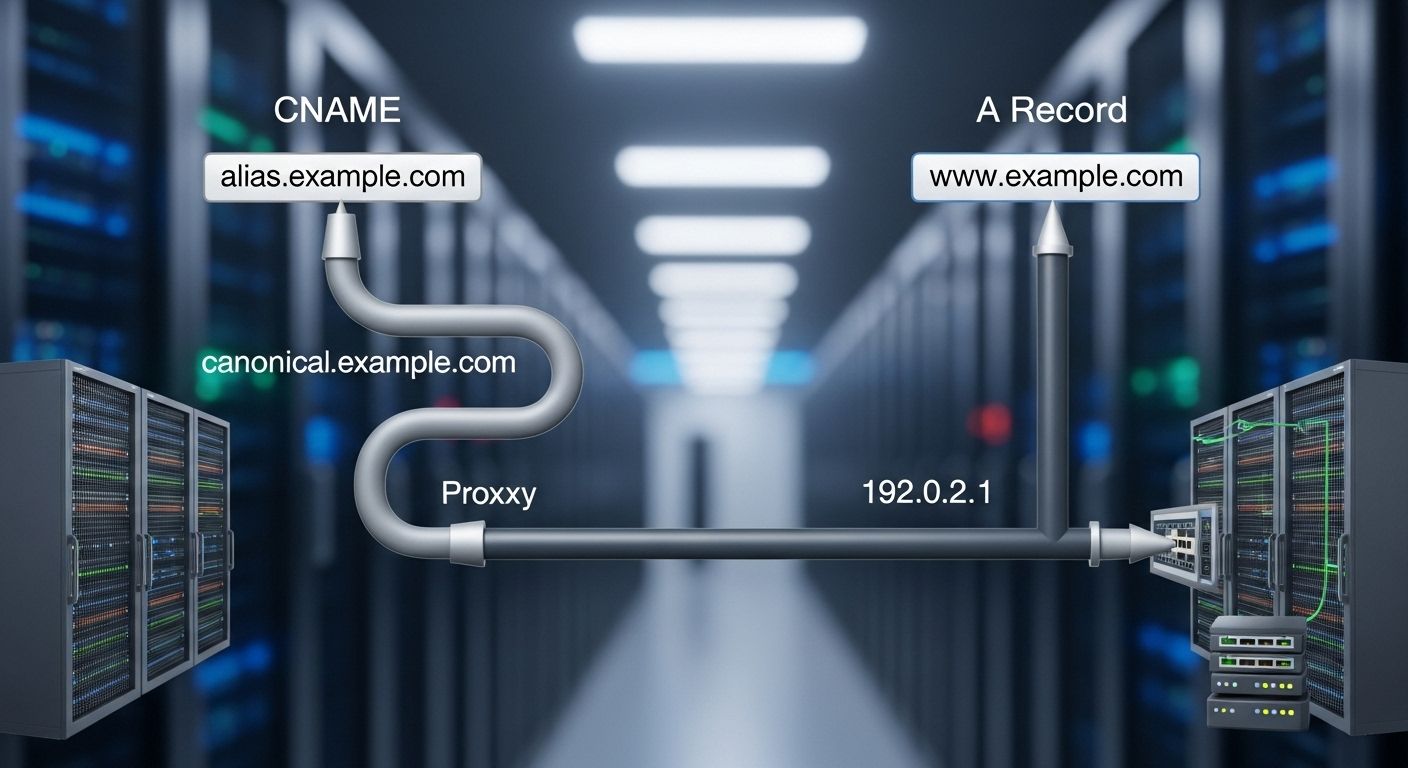

A CNAME—*Canonical Name*—is basically the DNS world’s forwarding address. It don’t point to no IP. Nah. It points to *another domain name*. Like tellin’ folks, *“My office moved—but just holler at ‘hq.peternakdigital.com,’ and they’ll getcha sorted.”* Super handy when you got a CDN, or when your backend’s jumpin’ cloud providers faster than a squirrel on espresso. But—and this’s a big ol’ *but*—a CNAME record *can’t live at the apex* (that’s fancy talk for the naked domain, like peternakdigital.com). Why? ‘Cause DNS specs say: *“If a CNAME’s here, it’s the only record allowed. No MX. No TXT. No A. Just… it.”* And if you try? Congrats—you just broke email, broke verification, and probably made your boss question life choices. So yeah, cname record vs a record? It’s like tryna park a U-Haul in a Smart Car spot. Technically, maybe. *Should* you? Heck no.

Hold Up—Can You Even *Have* a CNAME Without an A Record?

Short answer? Technically, yes—but also… kinda no. Let’s break it down like cornbread. A CNAME points to *another name*. That *other* name? Gotta resolve *somewhere*. And ultimately? It’s gotta bottom out in an A record (or AAAA, for IPv6, but that’s a whole ‘nother rodeo). Think of it like a game of telephone: CNAME → alias → alias → … → *A record*. If that chain breaks? The whole thing crumples like a soda can in a bear hug. You *could* point a CNAME to another CNAME to another CNAME (we’ve seen folks do *five* deep—why, Timmy, *why*?), but DNS resolvers get cranky after ~10 hops, and your TTLs start lookin’ like a caffeine-deprived intern’s scribbles. Moral of the story: the cname record vs a record dependency ain’t optional—it’s *architectural*. No A record at the end? You’re buildin’ on quicksand, partner.

What Happens When You Try to Jam ‘Em Both in the Same Slot?

Alright, gather ‘round the campfire—this one’s a cautionary tale. Say you type this into your zone file: www IN A 192.0.2.1www IN CNAME cdn.example.com Boom. 💥 Conflict. The RFCs—the dusty rulebooks of the internet—say: *“A CNAME record MUST NOT exist alongside any other data for the same owner.”* Period. Full stop. Your DNS server? It’ll either: (a) ignore one (randomly—*thanks, BIND*), (b) throw an error loud enough to wake the neighbors, or (c) *pretend* it worked… until your site’s down on Black Friday. We saw a startup lose $22K in sales ‘cause their dev swore they “tested it locally.” Spoiler: localhost lies. A lot. So when you’re weighin’ cname record vs a record for the *same host*, pick one—and sleep soundly knowin’ your DNS ain’t holdin’ a grudge.

Y’all Seen That RFC 1034? ‘Cause It’s Got *Opinions*

Let’s get academic for a hot sec—but keep it real. RFC 1034, Section 3.6.2, straight-up says: *“If a CNAME RR is present at a node, no other data should be present.”* That “should”? In internet law, that’s closer to “*or else*.” It’s not a suggestion—it’s a structural constraint baked into how DNS caches, recursors, and resolvers *work*. Violate it, and you ain’t just breakin’ rules—you’re breakin’ *expectations*. Modern DNS providers (Cloudflare, AWS Route 53, etc.) sometimes bend the rules with *ALIAS* or *ANAME* records—clever workarounds that *look* like CNAMEs at the root but resolve like A records under the hood. But under the microscope? That’s still a synthetic A record masqueradin’ as a CNAME. Bottom line: the cname record vs a record boundary exists for *reasons*—and those reasons got names like “scalability,” “cache coherency,” and “not wantin’ the whole internet to sneeze.”

Real Talk: When Do You *Actually* Use Which?

Let’s cut through the jargon fog like a foghorn in N’awlins:

- A record: Use it for static IPs—your origin server, your mail server (MX needs it!), your root domain. If it ain’t movin’, A record’s your guy.

- CNAME record: Use it for *subdomains* that *follow* something else—like

www,blog,shop, orapi. Especially if that thing’s hosted on a third-party platform (Shopify, Netlify, GitHub Pages). Pro tip: if the target’s IP might change (‘cause CDN or load balancer), CNAME’s your MVP.

Here’s a lil’ cheat sheet we keep taped to our monitor (next to the “Don’t Panic” Post-it):

| Scenario | A Record? | CNAME? | Why? |

|---|---|---|---|

example.com (root) | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | Needs MX/TXT/other records; CNAME would break ‘em. |

www.example.com | ✅ | ✅ (but not both!) | CNAME if pointing to CDN (e.g., ghs.googlehosted.com). |

mail.example.com | ✅ Strongly advised | ⚠️ Risky | Some mail servers reject CNAMEs for SMTP—just don’t. |

cdn.example.com | ✅ (if static IP) | ✅ (if dynamic backend) | CNAME = future-proof when provider rotates IPs. |

And remember—when in doubt, ask yourself: *“Is this host ever gonna need *anything* besides one pointer?”* If yes? Skip the CNAME. That’s the cname record vs a record gut check.

Fun Fact: Some Providers *Fake* CNAMEs at the Root (and It’s Genius)

Now don’t go tellin’ this at DNS nerd meetups *too* loud—but some platforms, like Cloudflare and AWS Route 53, let ya put a “CNAME-like” record on the apex. They call it an ALIAS (Route 53) or CNAME Flattening (Cloudflare). Here’s the magic: you *enter* a CNAME, but under the hood, their resolver does a real-time lookup and returns an *A record* to the client. So to the outside world? It’s just an A record. No RFC violations. No broken email. Just slick, clean redirection. It’s like a ventriloquist—mouth moves like a CNAME, but the voice comin’ out? Pure A record. Sneaky? Maybe. Life-savin’? Absolutely. But don’t confuse it with *actual* DNS—it’s a provider-specific hack. If you switch hosts? That record might vanish faster than free donuts at a dev conference.

CNAME Chains: The DNS Equivalent of “Hold My Beer”

We once audited a config where app.prod.example.com → CNAME → lb-east.prod.example.com → CNAME → cluster-gamma.internal.example.com → CNAME → svc-7a9b.prod.internal → … *six hops deep*. Bless their hearts. Every hop adds latency (even if just 0.5ms), increases failure risk, and makes troubleshooting look like decipherin’ hieroglyphics after three energy drinks. RFC 1034 *recommends* max 8 CNAME hops—but honestly? Keep it under 3. Your SREs’ll send ya cookies. And if you’re wonderin’ how this ties into cname record vs a record? Every extra CNAME is another *dependency* on that final A record. One break? The whole chain goes *poof*. Not “404.” Not “loading.” *Nothing.* Like it never existed. Spooky.

How *We* Keep ‘Em Straight When the Coffee’s Run Out

Look—we been there. 3 a.m. PagerDuty alert. Site’s down. You’re half-caffeinated, eyes blurry, and every DNS record looks like ancient runes. So here’s our battle-tested checklist for cname record vs a record sanity:

- Root domain? → A record. Always. (Or ALIAS if your provider’s cool like that.)

- Subdomain pointing to a *service*? → CNAME. (e.g., GitHub Pages, Heroku, Vercel)

- Need MX, TXT, or SRV? → NO CNAME. Periodt.

- Can’t remember? →

dig +short example.com. If it ends in a number? A record. If it ends in a dot-com? CNAME. (Bonus: if it says “CNAME … CNAME … CNAME … timed out”? Go home. You done enough today.)

And *please*—for the love of uptime—don’t mix ‘em on the same host. We promise: Peternak Digital won’t judge ya for usin’ A records everywhere *if it keeps the site up*. Stability over cleverness, every. Single. Time. Meanwhile, if you’re knee-deep in DNS toolin’, swing by our Tools section—we got free zone file validators that’ll catch those sneaky conflicts before they bite. And if SOA records got you side-eyein’ your screen? We broke it all down in What Is a SOA Record? Explanation, Examples, and Why Your DNS Cares—no jargon, just truth and a lil’ sass.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can you have a CNAME without an A record?

Well, *sorta*—but not really. A CNAME points to *another domain name*, and *that* name must eventually resolve to an A record (or AAAA). So while you *can* have a CNAME alone in your zone file, the chain *must* end in an A record somewhere—otherwise? You’re sendin’ queries into the void. Think o’ it like a forwarding address: Uncle Joe can tell the post office, *“Send my mail to Cousin Ray,”* but if Ray ain’t got a real street address? Mail piles up in limbo. Same deal with cname record vs a record—the A record’s the brick-and-mortar. The CNAME’s just the forwarding slip.

What is the difference between DNS Type A and CNAME?

Ain’t no apples-to-apples here, friends. An A record maps a hostname *directly* to an IPv4 address—like peternakdigital.com → 192.0.2.1. Solid. Final. A CNAME record, though? It maps a hostname to *another hostname*—like www.peternakdigital.com → peternakdigital.com. It’s a *pointer*, not a destination. And crucially: you can’t mix ‘em on the same label, and CNAMEs break at the root. So in the cname record vs a record tussle? A records are the foundation. CNAMEs are the redirect arrows—useful, but *never* structural.

What is an A record used for?

An A record’s the workhorse of DNS—it’s how the internet finds your actual server. You type a domain, the resolver checks the A record, and boom: gets the IP address (like 203.0.113.42) to connect to. You need it for root domains (’cause CNAMEs would nuke your email), for mail servers (MX records *require* A/AAAA behind ‘em), and for anything that needs to be *stable* and *independent*. Honestly? If your site’s small and static, A records everywhere ain’t wrong. Keep it simple, keep it sturdy—that’s the cname record vs a record wisdom passed down from sysadmin to sysadmin, like a well-worn Leatherman.

Can I have both a CNAME and A record?

*Technically*? Your DNS editor *might* let ya save it. *Should* you? **Hell to the no.** RFC 1034 draws a hard line: *“If a CNAME RR is present at a node, no other data should be present.”* Try mixin’ ‘em on the same host (e.g., www IN A … and www IN CNAME …), and you’ll get inconsistent behavior—some resolvers pick A, some choke, some pick CNAME, and none of it’s predictable. It’s like installin’ two gas pedals in one car and hopin’ they sync up. Spoiler: they don’t. So when weighin’ cname record vs a record for a single hostname? Pick *one*. Your future self’ll thank ya—with coffee. And possibly pie.

References

- https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc1034

- https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/dns/dns-records/dns-cname-record/

- https://aws.amazon.com/route53/faqs/

- https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2181#section-10.3